Cordwainer Smith In Japan

10 10月 2024

The name Cordwainer Smith probably doesn't ring a bell in the English-speaking world, unless you're talking to a hardcore science fiction fan. He died too young at the age of 53 in 1966, having published only one science fiction novel, and his only real SF ouevre was a collection of short stories (a format not in vogue in the UK, and even worse treated in the USA).

And yet, his stories about the Instrumentality of Mankind depict a strangely beautiful future so unknown to our current moral standards. To read one of his stories is to step into the deep unknown. The Old North Australians have created an immortality drug from dying sheep, there is a mysterious realm called The Great Pain of Space discovered by the early pioneers of space travel, and humans working alongside cats to fight against space dragons:

"Meow." That was all she had said. Yet it had cut him like a knife.

"The Game of Rat and Dragon", one of the first Smith stories ever translated into Japanese, follows the adventures of Underhill, a telepath hired as a pinlighter to defend ships traversing across space. "Pinlighting," Smith writes, "consisted of the detonation of ultra-vivid miniature photonuclear bombs, which converted a few ounces of a magnesium isotope into pure visible radiance." In other words, the humans were defending themselves by nuking the dragons. But this was not enough as they needed the minds of the Partners:

Man and Partner could do together what Man could not do alone. Men had the intellect. Partners had the speed.

The Partners rode their tiny craft, no larger than footballs, outside the spaceships. They planoformed with the ships. They rode beside them in their six-pound craft ready to attack.

The tiny ships of the Partners were swift. Each carried a dozen pinlights, bombs no bigger than thimbles.

The pinlighters threw the Partners—quite literally threw—by means of mind-to-firing relays direct at the Dragons.

These feline Partners were not only unafraid of dragons but literally saw them as rats to be hunted down. These cats craved the chase, and even wished the encounter would last longer. This partnership finally allowed space trade to flourish.

For this excursion, Underhill is partnered with Lady May:

The Lady May was the most thoughtful Partner he had ever met. In her, the finely bred pedigree mind of a Persian cat had reached one of its highest peaks of development. She was more complex than any human woman, but the complexity was all one of emotions, memory, hope and discriminated experience—experience sorted through without benefit of words.

When he had first come into contact with her mind, he was astonished at its clarity. With her he remembered her kittenhood. He remembered every mating experience she had ever had. He saw in a half-recognizable gallery all the other pinlighters with whom she had been paired for the fight. And he saw himself radiant, cheerful and desirable.

He even thought he caught the edge of a longing—

A very flattering and yearning thought: What a pity he is not a cat.

The flattering thoughts continue in the present. After a "good" planoform jump, the Lady May sends him her thoughts, "O warm, O generous, O gigantic man! O brave, O friendly, O tender and huge Partner! O wonderful with you, with you so good, good, good, warm, warm, now to fight, now to go, good with you...."

The battle is fierce, but once again the humans and the cats win. Unfortunately, Underhill was grazed by a dragon and had to be taken to hospital. He worries about his Partner's health, much to the nurse's chagrin. She lashes out: "You pinlighters! You and your damn cats!" He peers into her mind, revealing that she despises his strength and beauty compared to hers. His mind wanders to the image of Lady May:

"She is a cat," he thought. "That's all she is—a cat!"

But that was not how his mind saw her—quick beyond all dreams of speed, sharp, clever, unbelievably graceful, beautiful, wordless and undemanding.

Where would he ever find a woman who could compare with her?

And yes, in case you're wondering, Lady May is one of Cordwainer Smith's many cats.

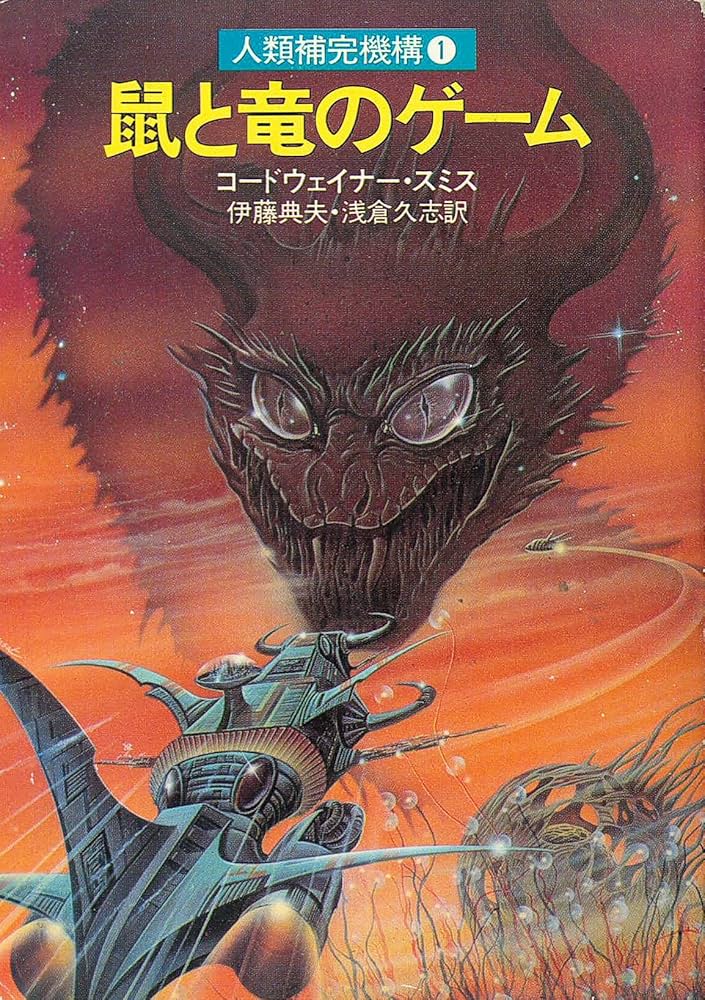

"The Game of Rat and Dragon" was chosen as the title for Cordwainer Smith's first collection of short stories in Japan. Published in 1982 and translated by Itou Norio and Asakura Hisashi, this book collects the first half of The Best of Cordwainer Smith, edited by John J. Pierce: "Scanners Live in Vain", "The Lady Who Sailed the Soul", the title story, "The Burning of the Brain", "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal", "Golden the Ship Was... Oh! Oh! Oh!", "Mother Hitton's Littul Kittons" and "Alpha Ralpha Boulevard". Some of these stories had already appeared in the popular SF Magazine, which is probably where the translations came from. It would be another 12 years before the second half of Pierce's selections appeared, this time entitled "A Planet Named Shayol" and translated only by Itou Norio. The "Shayol" story would later win the 26th Seiun Foreign Short Story Award in 1996. A few more stories outside The Best of were translated by Itou and anthologized in War No.81-Q in 1997. But the rest of his science fiction would not be translated and published until 2016, along with the existing stories, in three massive volumes following the authoritative table of contents of the 1993 NESFA print edition.

And that would be it if this article were simply about the publication history of Cordwainer Smith's work in Japan. He didn't seem to have much of an impact on the Japanese media (with one major exception, which we'll come to shortly), and his works seemed to suffer the same fate in Japan as they did in the English-speaking world: obscurity except as a cult favorite for the most dedicated SF readers.

But while his influence in Japanese media is minimal at best, he has impacted a more important community: the people who read science fiction.

For me, the promise of reading science fiction has always been to imagine something very different from my boring reality. It is, as Philip K. Dick writes in a letter dated 14 May, 1981, "the shock of dysrecognition" that makes science fiction exciting. The best science fiction revels in what he calls "dislocations", things that deviate from our known world and therefore become something else entirely. Readers should also be caught up in this mess. Science fiction should provoke us to speculate, to be creative alongside the author.

The best of Cordwainer Smith's stories seem to do this because they can be read like a mystery. The reader is thrown into a mysterious world and has to play detective to figure out neologisms like "cranching" or "planoforming" if they want to understand what's going on.

So, it must have been interesting to come across a catgirl in Smith's stories. While there are a few earlier examples of characters with cat ears (Hecate in Tezaku Osamu's Ribbon Knight), the recurring character C'mell seems to have caused many people to imagine what a catgirl might look like:

C'mell stared at the floor, her red hair soft as the fur of a Persian cat. It made her head seemed bathed in flames. Her eyes looked human, except that they had the capacity of reflecting when light struck them; the irises were the rich green of the ancient cat. When she looked right at him, looking up from the floor, her glance had the impact of a blow. "What do you want from me?"

Stories like "The Lost Ballad of C'Mell" give little insight into what she looks like. Like other Smith stories, she is described only in brushstrokes, nothing concrete. But her adventures and cunning personality must have evoked something: in 1985, SF Magazine printed an insert illustration by Katou Toshiaki for Oohara Mariko's 女性型精神構造保持者 (Joseikata Seishin Kouzou Hoshijya); it shows a catgirl looking into the distance, and she has the same hairstyle as C'mell.

This isn't a one-off either. She's appeared in long-lost doujin or fanzines from the 80s and 90s, as a character in Tanaka Yutaka's AI-REN, and as a race of catgirls in Liar-Soft's visual novel Cannonball. There must be more lost in the annals of time, considering she may be the main inspiration for catgirl designs all over Japan. And Karen Hellekson mentioned in the acknowledgements for The Science Fiction of Cordwainer Smith that her chapter on "Punchboat" appeared in the 1995 fanzine Alpha Ralpha Boulevard organized by the Instrumentality fan group -- a very interesting example of cross-cultural communication. SF Studies Vol. 29, Part 3 describes the "graphic representations one of Smith’s most famous characters, the cat-girl C’mell" as

rang[ing] from professional-quality paintings to manga-and-anime-style erotic drawings: C’mell is often drawn as nude or semi-nude, but the images always include cat-ears and sometimes a cat-tail.

And the art was likely drawn by Nagano Takeshi, better known as Nagano Grow-Psy. His website is still up, featuring a very cute rendering of C'mell. If you go to the page on Cordwainer Smith's work, you are encouraged to die buying his books, with each entry pointing the reader to the story she appears in.

This has led Japanese bloggers to describe the works of Cordwainer Smith as the grandparent of all cat ears-themed science fiction.

The stories she came from are part of a series of stories called the Instrumentality of Mankind. Each story reads differently as they can be centuries apart, depicting different phases of humanity, aliens and technology; the earliest begins in 2,000 AD and the latest ends around 16,000 AD, allowing for a continuous yet fabulous timeline that seems to stretch the human imagination.

For example, in "Alpha Ralpha Boulevard", the same story that introduced C'mell to the world, set in 16,000AD, the reader is introduced to the Rediscovery of Man:

We were drunk with happiness in those early years. Everybody was, especially the young people. These were the first years of the Rediscovery of Man, when the Instrumentality dug deep in the treasury, reconstructing the old cultures, the old languages, and even the old troubles. The nightmare of perfection had taken our forefathers to the edge of suicide. Now under the leadership of the Lord Jestocost and the Lady Alice More, the ancient civilizations were rising like great land masses out of the sea of the past.

This need to remember mortality and different languages is a far cry from "earlier" stories like "The Game of the Rat and Dragon", which is set in 9,000AD. There are many innovations that have changed humanity so much that it felt the need to "rediscover man", but we can also say that the main protagonist and antagonist of the story is the titular organization.

The Instrumentality of Man is a vague organisation that used to be a police force, but ended up ruling space and supposedly working to improve the lives of humanity in the coming space ages. But as Hellekson writes, the notion emerged much earlier in his historical fiction, Ria, written under another penname. She quotes the ending of the book, in which the titular disabled character lies in bed and feels like she has become larger and "listened to the fluent deep roa of a resounding bronze instrument of some kind — something metallic, something which sounded like the instrumentality of man, not like the unplanned noises of nature and the sea." Hellekson continues,

Instead of coming to terms with a traumatic experience in her childhood, Ria has to come to terms with the resonances of her own life, with the “instrumentality of man” that suggests humans can affect their own destinies. Her remembrances of Bad Christi serve not to cure her paralysis but to indicate an opening through which she has to travel in order to come to terms with her life. Only then is she in a position to overcome her physical disability. Her fifteen-year-old self is not in a place to affect her own destiny; indeed, her lack of control over herself, her emotions, and others distresses her in Bad Christi. Her thirty-six-year-old self, on the other hand, has gained some mastery over the instrumentality.

Whatever Smith has in mind, the Instrumentality seems to be a literalisation of the need to perfect the human condition. The science fiction organisation that bears his name "usurps nature's job", to use Hellekson's phrase. Its eugenicist policies are so successful that the implementation of the Rediscovery of Man is deemed necessary to retract its successes. Yet, its goals remain noble: the underpeople which include the catpeople like C'mell and humanity share a common destiny and something major will happen.

Unfortunately, he passed away before he could finish writing the "Lords of Afternoon" novels that would have completed the timeline. As John J. Pierce wistfully laments in his essay "Cordwainer Smith: The Shaper of Myths",

Smith's universe remains infinitely greater than our knowledge of it ... Then there is that unfulfilled sense of anticipation -- where was Smith leading us? What comes after the Rediscovery of Man and the liberation of the underpeople by C'mell? Linebarger [Cordwainer Smith's real name] gives hints of a common destiny for man and underpeople -- some religious fulfillments of history, perhaps. But they remain hints.

I've read all of Cordwainer Smith's science fiction and I'm left with a sense of emptiness of what might have been. When I read his first published story under that name, "Scanners Live in Vain", I was intrigued and compelled by his strange dystopian world. In fact, his weaker stories are those that are too close to human history and "real life"; I am repelled by his conservative politics (the author was the godson of Sun Yat-sen and worked for the Kuomintang and the United States during the Chinese Civil War), his concept of gender is very heteronormative, and I can't say I'm fond of his later turn to religion and psychoanalysis. His best works are, on the other hand, truly out of this world.

I can't imagine anyone writing this, except maybe an alien trying to write science fiction for us humans. Cordwainer Smith's writing is simply of a different breed. I want to know what the Instrumentality of Mankind actually is.

Well, I've got my answer of sorts. I'm, of course, talking about Neon Genesis Evangelion. In Anno Hideaki's masterpiece, the Instrumentality of Mankind has become a pet project of the SEELE organization: the forced evolution of humanity through the Third Impact. The Instrumentality differs between the TV series, the films and the print materials, but they all relate to humanity evolving into a collective existence. The flaws of individuals are complemented by the strengths of others, hence the original ADV English dub and early fan translations call it the Complementary instead as they seem unaware of the reference.

There are major differences between the Instrumentality of Mankind (人類補完機構) and the Human Instrumentality Project (人類補完計画). For one thing, the earlier Japanese translation refers to an organization or structure, usually within states. There is also a religious connotation, as in "instrument of the gods": there is supposed to be a mediator between the gods, the humans, and the underhumans. The Human Instrumentality Project, on the other hand, is not concerned with this role. It is just a project, a means to an end. It only appears at the end of the TV series, and its consequences are only explored in the Rebuild series, specifically 3.0 and 3.0 + 1.0, whereas Smith's work is concerned with how the goals of the Instrumentality and the perfection of the human condition have changed throughout history. And while both works have tensions with their Instrumentalities, Evangelion is far more sceptical while Smith seems to believe in a possible future that actually adheres to the ideal of the Instrumentality, which is described as a kind of religious awakening.

It's thus clear that Anno and Smith have different preoccupations about what humanity ought to be, which may explain why there are almost no English or Japanese essays that I can find discussing possible thematic connections in each other's works. At most, people will acknowledge the origin of the term, and that's it. I have little to say about this connection, but I think there might be something interesting, especially in the context of the last Rebuild film.

I just had to bring it up because it's Evangelion, you know.

The trail grows cold again. Cordwainer Smith is just not a popular writer unless you're really into science fiction, even if he is critically acclaimed. It doesn't matter if popular authors like Terry Pratchett or anime like Evangelion mention him.

His stories don't really fit in with the expectations that people tend to have of science fiction.

That may be why Oono Maki, a science fiction critic and translator, wrote their 1980 article for SF Magazine the way they did:

コードウェイナー・スミスの名を知っていますか? 知らなくても、別に恥ではありませんが、この機会に覚えておいて下さい。知っているとなかなか便利なものです。たとえば、あなたがどこかのSFファングル?プに人って、初めてその会合に出かけたとします。あるいは、SF大会とかフェスティバルとかで、いかにもSFマ二アという顔をした連中と話をしなければならなくなったとします。おそらく、その異様な雰囲気に、あなたは圧倒されてしまうでしょう。連中は、SFのことなら何でも知っているという顔をして、初心者のあなたをもてあそぼうとするのです。いかにも優しそうににこにこしながら、たとえば、「SFでは、どんなのが好き?」と訊いてきます。(最近ではこんなこと訊かないのかなあ?)

あわててはいけません。ここでうっかりしたことをいうと、後々までたたります。もちろん、まずあなたが本当に好きなSF作家の名前をあげなければいけませんが、敵があまりにもマニアマ二アした顔をして「ふん、ふん、かわゆいね」てな感じで訊いている場合には、最後にひと言つけ加えるのです(どういうのが〃マ二アマ二アした〃顔かといいますと、見本をお見せするのが一番いいんですが、まあ、ひと目見ればわかると思います)。

「それから、コードウェイナー・スミスとか……」

このひと言で、相手の態度ががらりと変わるはずです。変わらない場合、その相手のマニア度は、そうたいしたものじゃない、と判断してさしつかえありません。 もっとも、あまりやり過ぎてはいけません。やり過ぎると、「またか」と露骨に嫌な顔をされたり、場合によっては「SFの話をするやつはきらいだ」などといわれたりします。後者のような場合には、「マ二アだって人間なんだ――」と小さくつぶやいて、なるたけ早く立ち直ることをお祈りします。

Do you know who Cordwainer Smith is? Don't be ashamed if you don't, just remember his name next time. Knowing his name can be quite useful. Let's say you're joining a science fiction club and you're going to your first meeting, or you're at a convention and you have to talk to people who look like science fiction enthusiasts. You'll probably feel overwhelmed. They might assume you're a beginner, smile at you, and ask, "What kind of science fiction do you like?

Don't panic. If you say something that doesn't sound good, it'll come back to bite you later. Of course, you should mention your favourite sci-fi author, but if your opponent is asking you with a geeky grin on his face, you should get the last word (a quick way to know if they're that kind of person is to bring something innocuous up, but you'll probably know if they're like that from their face):

"Well, I'm into Cordwainer Smith and..."

This should change their behaviour towards you. If it doesn't, they might not be the nerd they claim to be. Just don't overdo it. People may grimace at you before saying "Not again", or they don't like talking to people who only talk about science fiction. In the latter case, you could try to deflect the criticism by pointing out that geeks are people too...

Oono admits it's a silly way to start an article about the timelessness of Cordwainer Smith, but their point is well made: people who are into Smith are going to be extremely passionate about science fiction. Compared to the likes of Tiptree Jr who is popular in Japan, Smith doesn't have the same mass appeal. His fiction defies typical science fiction categorisation: it is hard and soft science fiction, with narrative techniques borrowed from Chinese legends.

But as they write in 2016, reviewing one of the new short story collections,

コードウエィナー・スミスこそ、SFというジャンルを超えて、半世紀以上も前に、オタク文化、萌え文化を先取りしていたといえるのではないだろうか。もちろんスミスの魅力はオタク的要素だけにあるのではないが、少なくとも日本でのスミスの受容史を見てみると、”萌え”も含めたオタク的・マニア的感性への親和性こそが、スミスをここまで特別なものにしたのではないかと思えてくる。

Beyond the realm of science fiction, Cordwainer Smith was a forerunner of the otaku and moe subcultures more than half a century ago. His appeal is not only in the otaku world, but if we look at his reception in Japan, he has a strong affinity with otaku and geek sensibilities, including an appreciation for moe. This may be what made him so special.

I have to agree, especially since C'mell isn't the only cute girl around. The human sailor Helen America, the dog-girl D'joan, and the various women in The Quest of the Three Worlds all have developed backstories that wouldn't be weird in a visual novel published in the 90s and 00s.

And then, there's Smith's obsession with all things feline, an element much appreciated by Japanese readers. I don't think it's a coincidence that the first Japanese short story collection took its title from a short story about cats fighting dragons/rats.

It's almost as if he's writing for the current generation of otaku, before they were even born. For me, this makes his writing almost timeless in the context of Japanese media: his stories contain elements that appeal to an audience that is watching anime and reading manga right now.

There are many reasons why I find Cordwainer Smith's writing so fascinating: it taps into the political tensions of the Cold War, his stories force the reader to imagine a bizarre future, and so on. But what strikes me most is how familiar his writing is, because it resembles the kind of vibes I've been looking for in Japanese media since before I learned Japanese.

I open up a random page of my copy:

Human flesh, older than history, more dogged than culture has its own wisdom. The bodies of people are marked with the archaic ruses of survival, so that on Fomalhaut III, Elaine herself preserved the skills of ancestors she never even thought about -- those ancestors who, in the incredible and remote past, had mastered terrible Earth itself. Elaine was mad. But there was a part of her which suspected that she was mad.

This random passage from "The Dead Lady of Clown Town" is evocative, if alien to me. What happened on Old Earth? I know some details from other stories, but I don't know much about Fomalhaut III, for example. I start to have questions and populate my mind with different worlds that passage has provided for me.

If Philip K. Dick is right that science fiction should inspire its readers to create, then Cordwainer Smith may be one of the most successful science fiction writers, despite his lack of reputation. Would otaku culture be like this if C'mell had not inspired the design of catgirls in future works and Anno had not taken the name Instrumentality from Smith's works? It's hard to say, but if true, he might be one of the best science fiction writers in history.

Who would have thought that an American writer who died in 1966 could have played a small but important role in the formation of Japanese media subcultures? Japanese media isn't just Japanese, it's an amalgamation of influences that go beyond the geographical region of Japan. People in Japan read writers from other countries, adopt and question ideas from foreign cultures, and so on. When writing about Japanese media, it would be a mistake to focus on what is written in Japanese. Otherwise, we could be missing someone as interesting as Cordwainer Smith.

Other Notes

For those who want to read Cordwainer Smith in English, there are two main versions of the work, both bearing the same name: The Rediscovery of Man. The more accessible one, Gollancz's Masterworks, collects only a handful of stories previously collected as The Best of Cordwainer Smith by John J. Pierce. The complete works is a massive tome published by NESFA in 1993, and it is the standard version used by scholars.

Some of the stories are in the public domain. If you're unsure about taking the plunge into Cordwainer Smith's fiction, I'd echo the recommendations of many fans: start with "Scanners Live in Vain" and "A Game of Rat and Dragons". If you like those two stories, consider buying either book. Both versions are fine, but I think Pierce has more or collected the best stories.

I would have liked both books to arrange the stories not in chronological order but in order of publication. Oh well. Anyway, my favorite story might be "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal". The Gender in that story is wild.

People familiar with the myths surrounding Cordwainer Smith may be surprised that I haven't mentioned Kirk Allen here. I've written my thoughts on the subject in another blog, so have a look.

I'm also interested in writing more articles about the Japanese reception of foreign writers. Not only do I enjoy uncovering crosscultural interactions like this, but I also think it would be useful for the Kansoulations project. I'm envisioning Kansoulations not just as a book review blog but as a site that explores print media (Japanese and otherwise) and their influence in Japan. It allows me to write about nonfiction for example. Let me know if this is something you'll like to see more.