To The Moon Is A Mess I Wanted To Love But Was Instead Hurt By

15 4月 2024

This post will discuss topics on autism, ableism, and other adjacent subject matter. And there's going to be spoilers because there's really no way to go around it.

How I Learned of the Game

To the Moon is a groundbreaking RPG Maker XP game. As a commercial title, it predates titles like Dear Esther by focusing on narrative and dialog. It deals with autism at a time when the term was used to denigrate people who were different. And it may be one of the earliest games I know that uses the term "neurotypical".

I've known about this game since it came out in 2011, but I kept putting it off because I wasn't that interested in what was being marketed as artistic and important in this era of Premium Indie Games. That all changed when I saw this still excellent video from Questing Refuge:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znWjY70dAA4

The argument is simple: even though we have more media focusing on autistic characters these days, To the Moon somehow still hits. They make a clear case that the game is impressive because it features a late-diagnosed autistic woman (still deeply underrepresented) who doesn't have any kind of savant-like abilities; it also features another autistic character who is different from the main autistic character. The game also challenges the premise of manic pixie dream girls while addressing real-world issues. This all sounds appealing to me, especially as someone who is dating a late-diagnosed autistic partner and is also the uncle of a non-verbal autistic nephew.

It's the kind of work I'd like to read about because there's never enough good information about autistic people. For better or worse, I went into it with slightly higher expectations because it's such a well-received work and it was highly praised by a very cool autistic parent video essayist I follow. I also streamed the game to my partner because I knew it was a short game that they might be interested in.

Narrative Game Design Before Narrative Games

You follow two scientists/engineers who are contracted to manipulate the memories of Johnny, a dying man, to fulfill his wish of going to the moon. To make this happen, they have to go into the recesses of his childhood memories, implant the desire there, and make him "relive" his life where he could finally fly to the moon before he dies. It was such an odd premise that my partner quipped that they could see the ethical implications on the horizon.

Nevertheless, I find the premise working well with the RPG Maker engine. To get deeper into his childhood memories, you must guide the scientists to find objects that create enough memory links to find the one symbolic object that will allow them to traverse to an earlier part of his memories. Most interestingly, the game never explains that this is what you have to do. You learn it through the techno-babble tooltips and just by interacting with the world. I thought this was quite effective because it made me feel like I was connected to the scientists who were exploring the psychological worlds of Johnny while giving him a memorable personality. We learn that he's very fond of pickled olives, an object that one of the scientists finds disgusting for some reason.

Each memory is also full of original assets, so locations have their own distinctive feel to it and nothing feels recycled. I was surprised by the mansion and town fair maps in particular. The maps are also quite small; you'll never get lost in these places, but they're also large enough to function as visualized and interactive memories.

That said, assets are probably too detailed compared to other RPG Maker XP games since there is no yellow paint to indicate what is an interactable object and what isn't. But the few moments where I was temporarily stuck didn't matter too much. There is one part that sticks with me though: in the therapist memory, you have to stand on a certain spot on the couch in order to get the McGuffin to advance the game state. I think the intent is that it's a spot where Johnny is anxiously sitting for their turn, but I found this vague and questionable.

In most cases, the game has very recognizable objects and intuitive places that make a lot of sense as to why Johnny would find significant meaning in them. It's rewarding to make educated guesses and get one step closer to understanding what's going on with Johnny.

River and Johnny

But Johnny is not really the main star of the game. As we delve into his world, we learn that his life revolves around River, his spouse. She is the main reason why people remember this game so fondly and why autistic people find her portrayal so meaningful. However, she's also a mystery to the avatars we control and even to the person she's married to.

Before the scientists jump into their memories, you can take control and explore the mansion with the caretaker's children. There are many origami paper rabbits in the basement. In the lighthouse, we also find a multicolored paper rabbit. There are also several photos in the bedroom, including one of a strange animal (later revealed to be a platypus). All of this seems strange to everyone (and to the player as it keeps adding some jumpscare-like BGM).

The game doesn't hide who made the paper rabbits: in a few minutes of gameplay, we learn that they were all made by River. As we enter the memory where she begins to fold the paper bunnies, she interrogates Johnny, asking him what he thinks of the paper bunny. Johnny responds by describing the quality of the paper and the color of the rabbit. And she continues to fold rabbits in silence.

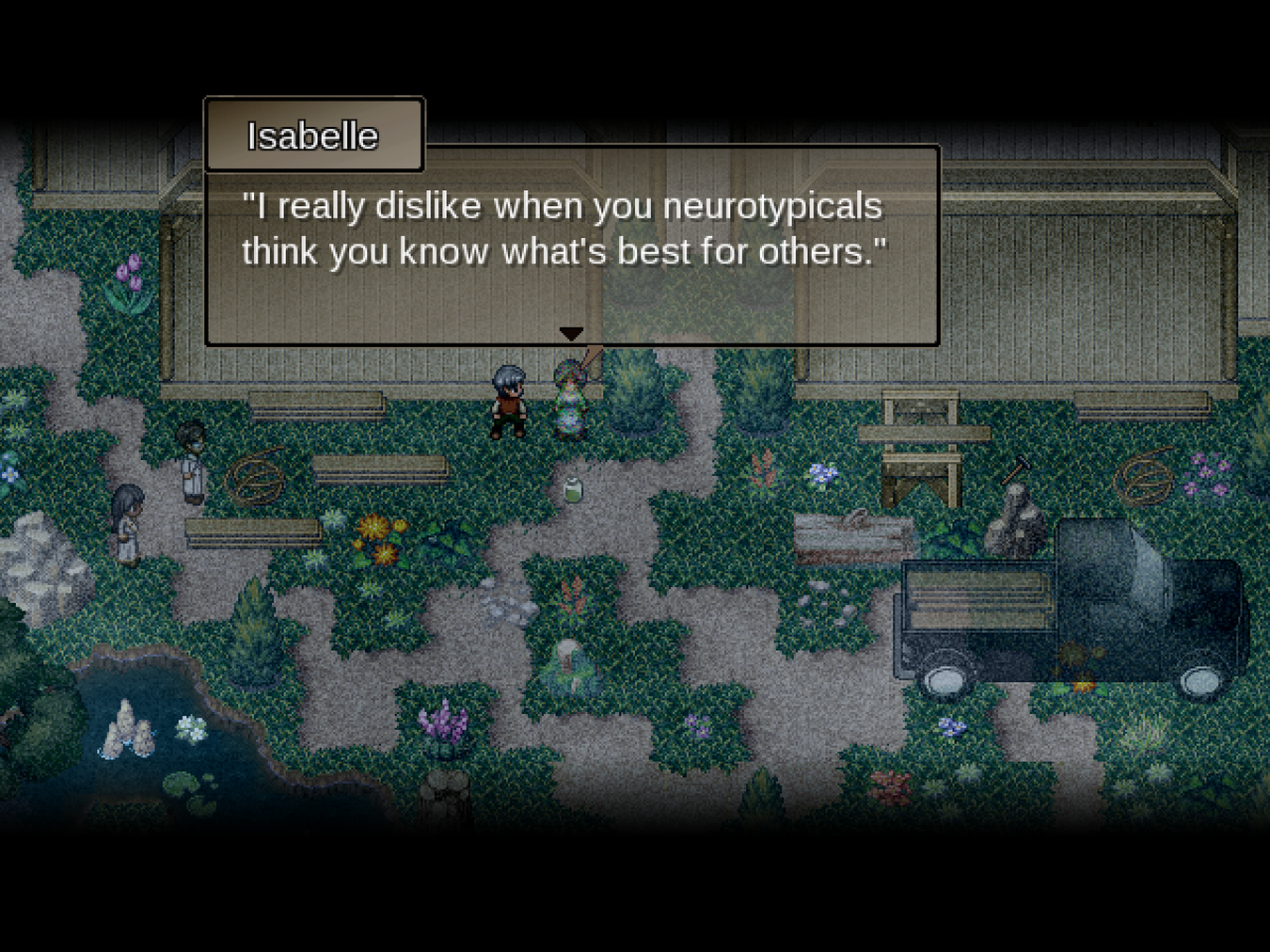

Past memories continue to tease the tension between what should have been a loving couple. Johnny doesn't understand the person he's married to and asks Isabelle, an autistic friend of the couple, to explain to him why she acts the way she does. In the therapist's memory where River is officially diagnosed as autistic, Johnny refuses to read the book about the condition. And in one of his earliest childhood memories, he admits to a friend that his interest in River is that she's different and strange, completely removed from his typical life. Perhaps, being close to her will help him find a different life altogether.

This was all fascinating to my partner and me. We were initially concerned about the game's treatment of River as an enigma; however, the game -- especially with the introduction of Isabelle -- shows that the game's framing comes from Johnny's neurotypical fetishization of autistic people. He may have loved River and he at least tries to give her space by following the therapist’s recommendation to do equine-assisted therapy, but he doesn't seem to care about how she thinks. When she asks him about his old obsession with Animorphs and why he left the books in the boxes, he says he's grown out of it and seems confused that River would ask that. It's such an interesting exchange because it subtly shows the difference between the two characters: River cherishes childhood memories while Johnny neglects them. It also works as a microcosm of their relationship because Johnny, like other neurotypicals, is more interested in the big picture while River is fixated on the specific. There is a distance between them, and we found it very compelling that the game touches on that.

It is obvious that Johnny regrets what he did to River. His reluctance to empathize with her made their relationship shaky, and his desire to go to the moon is clearly related to finding a way to reach her. But that seems like a lost cause: she died before he did, and he still doesn't know what she means by the symbolism of paper rabbits and lighthouses. He will die an unhappy man, unsure of what River wants from him and what he really wants.

Unethical and Unfunny Implications

This is where Sigmund Corp. comes into play. To the Moon is the first episode of a series of games depicting the scientists and engineers creating artificial memories by manipulating old childhood memories and the unethical implications of doing so. The premise is definitely fascinating and creates interesting conundrums for the player and characters.

However, this premise isn't explored in To the Moon itself and for a long time, it was the only game in the series. It also didn't help that we have to control two very unlikable avatars who seem like they're from the worst sprite webcomics imaginable.

Dr. Eva Roselene and Dr. Neil Watts are not very good characters, and they are a symptom of the game's larger problem: its humor. I've put these two characters on the backburner for a long time because I don't think any of their dialog is really relevant to the story -- if anything, it's detrimental to the game.

I can see where the writers are coming from. This is supposed to be a series, so it makes sense that the characters we follow have strong personalities who then struggle with their ethical code as they continue to do this job. This is especially clear when they agree with the player that Johnny is kind of an ass and they aren't sure how making him an astronaut will clear his abuse toward River.

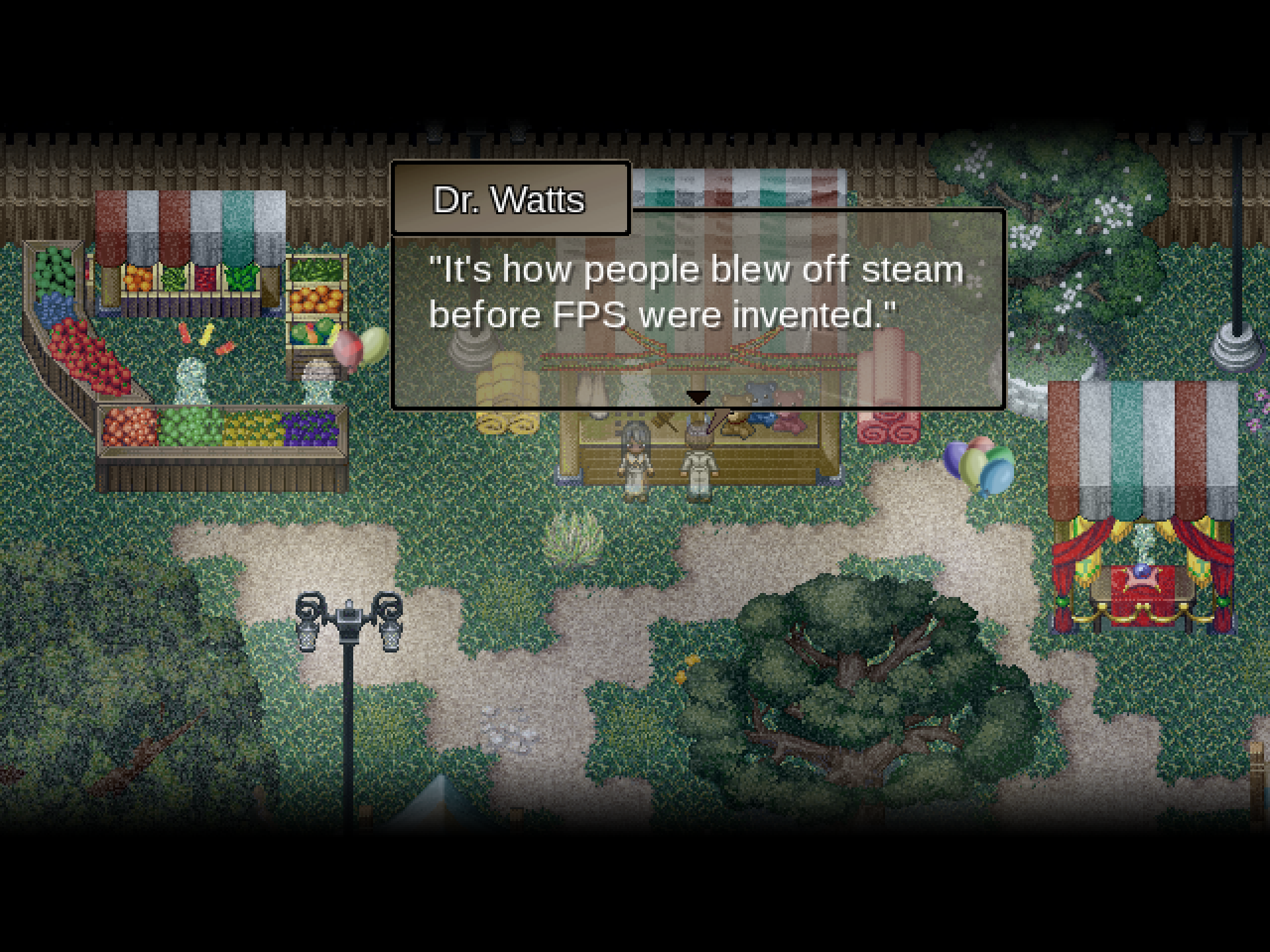

However, they also make jokes like this:

Instead of acting like professionals with a little history, they act more like high school students role-playing how business colleagues should act. They bicker for too long, make so many wisecracking jokes, and are so generally disrespectful to each other that you want them to shut up. Their dynamic is so fundamentally hostile that the few times the player would agree with them about the situation feels like a mistake.

I find their appearance intrusive to the atmosphere of To the Moon. Actual moments of emotional resonance are ruined by Eva telling Neil not to say what he is about to say, or Neil shouting hadouken. I understand that the comedy is a product of its time, but it's extremely difficult to ignore when it's sometimes the punchline to an emotionally effective scene. They don't strike me as people who are willing to grasp the unethical underpinnings of their work at all.

Beta Blockers, Memory Loss, and Twin Brothers

Even though the protagonists were obnoxious, my partner and I were willing to ignore them as much as possible because we found the game very interesting. Unfortunately, when we started the game, we entered the second half of the game and found ourselves disgusted and even harmed by it.

Eva and Neil discovered that they couldn't get to Johnny's earliest memories, and that's quite a problem because they can't make him realize his dreams of being an astronaut with what they have. No matter how much mischief they have caused, nothing has changed his circumstances.

While Eva ponders the meaning of River to Johnny, Neil calls his office only to discover that Johnny has been taking beta blockers, which are associated with memory loss in people with cognitive disabilities. I thought this was a rather contrived plot device as you could say that Johnny is taking them to deal with his traumatic experience to be discussed soon, but it's the kind of thing that people in this business should already know.

We finally enter the first of three blocked memories where we learn that Johnny had a twin brother named Joey, and that the boy was hit by their mother's car. This explains why his mother keeps calling Johnny "Joey" because she has, in the wise words of Eva, "gone cuckoo." It also turns out that Joey was the one who was into Animorphs, not Johnny. And finally, we come to the earliest memory, which takes place at a town fair: Johnny wanders away from the fair and looks up at the stars; a young River approaches and says he's taken her place, and they both look at the stars (described by River as lonely lighthouses) and promise each other that if they don't find each other, they'll regroup at the moon.

I'm not sure I like this sentimental direction, because it suggests that

1) The reason Johnny became obsessed with the need to feel different is because he had an inferiority complex about his deceased twin brother. This over-explains a very common feeling neurotypicals have toward neurodivergent people since it absolves them of responsibility for learning to empathize with them.

2) It cheapens River's struggle to be understood. She wants Johnny to remember their childhood together, and that's fine. The paper rabbits come from him describing the rabbit-like shapes in the moon and she wants him to recall that, but the beta blockers serve as a very convenient explanation for why Johnny can't remember. It throws away the whole "neurotypicals forget the details while neurodivergent people are sensitive to them" dynamic so that Johnny can look like a redeemable figure. See, he didn't choose to forget -- it was this one plot device that made him forget.

But the game takes an even more bizarre step: Eva suddenly realizes that she has to "move" River into Johnny's memories if they are to fulfill the contract to deliver him to the moon. Neil doesn't want that, so we enter an epic RPG Maker horror-style gameplay segment where we have to dodge zombie Evas and spike with epic music blaring in the background. Despite all this, Eva has disappeared during the fateful encounter between River and Johnny while leaving Joey alive. Eva assures Neil that she trusts River to do the right thing.

We then get a montage of old memories with River being rewritten to the tune of some boring vocal interlude, and Johnny joining NASA. After we do the basic gameplay loop for the last time, Eva hesitates, wondering if she will come. Johnny is now ready to be an astronaut -- and then he is introduced to his astronaut partner, River.

The game ends with the player characters watching the rocket fly to the moon from a bridge. Both Johnny and River are on the rocket, of course, and we see flashes of them getting married under the lighthouse and so on.

The end. A happy ending for Johnny and a good job well done for our protagonists. And the game lets you know that there are sequels to this game. I immediately uninstalled the game and my partner and I groaned in pain from the entire endgame sequence. It might be one of the worst endings I've ever experienced because it actively hurt us.

What We Took Away From the Ending

I know our interpretation will be quite controversial for people who know the series and those who found meaning in the game. I'm not going to deny those readings because we certainly lack the context of the series, but I think it's too hard to ignore what the game did to River as a character and how the game seemed okay with it.

Everyone agrees that the ending is about rewriting Johnny's memories to fulfill a rather shallow wish. I think there are two main camps for reading this ending:

1) The cathartic bittersweet read: even though it is shallow, it is still somewhat fulfilling because it respects the wishes of everyone involved. My partner and I saw this as the goal of the ending.

2) The black-pilled nihilistic read: Nothing was accomplished except to satisfy Johnny's own ego. Many people, often people familiar with the series, have this reading.

I would prefer to read the game in 2), and it seems the series was headed in that direction. A friend of mine said that the first minisode explicitly addresses the dilemmas of the setting, which makes this reading very useful in the long run. It's also lampshaded by Neil who says that it's fucked up to remove someone so important to him just so he can go to the moon.

But without further context, I don't really have any reason to read it as 2). There are a few reasons why:

- The presentation, especially the montage, is pretty saccharine and wants you to sniffle at the moments in which River disappears.

- The climax depends entirely on Eva not explaining her actions to Neil and instead keeping the player guessing about her intentions. She often mentions how much she trusts River.

- River actually meets Neil at NASA, and it's presented as a nice reunion.

- And finally, no one really comments on how bizarre this is. Everyone seems satisfied with the way the plot of the game resolves itself and the characters move on to their next job.

I can easily believe that the writers are actually trying to do 2), but I think the 1) interpretation is just too strong. And I think this is how most people who write about To the Moon saw the game when it first came out: people were crying about this relationship being given new life, not getting depressed about how fucked up it is.

And I really hate the 1) ending because it downplays River's struggles and gives Johnny a get-out-of-jail-free card. It lets Johnny die a happy person and everyone is just fine with that. It's not just an unsatisfying ending, it's a deeply offensive and hurtful one.

Conclusion: Maybe, Sentimental Endings Suck

I don't want to hate this work. There have been much worse mainstream works that have portrayed autism and have worsened our understanding of it. To the Moon came from a real source of compassion for neurodivergent people and their diversity. There are educational aspects that remain timeless and while the humor hasn't aged well, the gameplay loop is engaging.

It's objectively a good narrative game worth studying by game designers and storytellers interested in narrative games and representations of neurodiversity.

The ending, however, sucks ass. It dilutes the complex relationships between neurotypicals and neurodivergent people for cheap emotional spectacle without fully committing to its setting and ideas. The first two hours made for a flawed gem of an experience, the last two hours a painful and frustrating one for my partner and me.

Ultimately, I see the game as an interesting, if hurtful, work of historical importance. At the very least, the errors I've identified mean that it's something I can explore in my own writings. I don't regret playing the game nor do I want to erase my memories of it.

I just want to remember the pain, so I can hopefully make something more meaningful than To the Moon.