Zambot 3 Is An Empty Symbol Of Justice That I Want To Buy One Day

13 8月 2024

This post will have unmarked spoilers for Zambot 3, the Berserker novels by Fred Saberhagen, and explore their themes of violence, history, and Zambot 3's final two arcs starting from episode 16 to the end.

An Interview with the Zambot

I first heard about the influence of Zambot 3 when I stumbled upon an interview between Yokoo Tarou of NieR: Automata fame and Tomino Yoshiyuki. Yokoo awkwardly and nervously babbled about how he saw stories as building blocks and what made video games unique while Tomino asked insightful questions and listened intently. I've never seen these two creators, so characteristically abrasive in interviews, become so docile and seemingly respectful of each other's work. It was a surprisingly wholesome watch.

At the very end, Yokoo mentions that he is part of a generation that has learned to tell stories about protagonists who do not have to be totally righteous and antagonists who have a reason to fight because he grew up watching Zambot 3.

I knew about Zambot 3 as the first original directorial debut of Tomino. But other than the fact that it's a super robot show that has appeared in several Super Robot Wars I've played, that's all I really knew. I was in a Tomino mood after rewatching Char's Counterattack, and the only non-Gundam Tomino show I've seen is Ideon -- I figured it should be easy to watch since it's only 23 episodes.

Let's just say I didn't know what I was getting into.

Japan, 1977

The first thing you see in Zambot 3 is Jin Kappei, a hotblooded rascal, riding a motorbike through the small fishing village by Surugawa Bay. His rival, Kouzuki Shingo, and his gang of bikers have him surrounded and are getting ready to give him a beating until the cops arrive on the scene and chase Kappei. All of this is happening as aliens from outer space, the Gaizok, begin their invasion of planet Earth.

From the first few minutes of the show, we get something very different from what you might expect from a mecha anime or science fiction as a whole. The show zooms in on the daily lives of the people in these fishing towns, trading ports, and even a Shizuoka town near Mt. Fuji that are being disrupted by the Gaizok. Later, we see white-collar workers on trains in cities as far away as Hakodate and Sendai. We are not watching Blade Runner but a post-WWII Japan that is still in the process of developing itself.

The only thing that can save Japan from total destruction is a bunch of mecha and ships left behind by Kappei's alien ancestors from long ago. This will require the combined efforts of the entire Jin family. While Kappei flies the Zambot Ace, his cousins Uchuta (Tokyo) and Keiko (Shinshu, now part of Nagano) fly the Zambull and Zambird, respectively. The three branches of the Jin family also fly three ships that can be combined into a mega-ship called the King Beal.

There's a lot of things going on that must make it bizarre and unusual for the kids watching the show as the episodes came out. This was the Japan they can see from their windows. They could picture the Zambot defending Osaka Castle and other familiar sights from the brutish Gaizok. They might also imagine that their cousins from far away are in the same struggle against evil. It's a kind of fantasy that invokes the unifying power of Japanese families in the '70s against this unknown evil: what if we all banded together and fought for justice?

A Kami for Our Own Purposes

However, this familial fantasy is often overwritten by the violence of the show and the suspicion from other Japanese people. The first half of the show is depressing to watch: the Japanese citizens, unaware that other countries like France quickly fell to the Gaizok, believe that the Jin family was the reason the Gaizok came to Earth. If the Jin family hadn't fought the Gaizok, if their ancestors hadn't come to Earth, perhaps the conflict could have been avoided altogether.

Their beliefs doesn't simply come from ignorance. The way Kappei fights the Galzoks is often very reckless, and it doesn't feel like the Jin family is actually winning. He is following in the footsteps of many hot-blooded protagonists of super robot shows before him, and the ends will justify the means in the long run, but the consequences go very deep into the show. His friends from the fishing village will go as far as Hakodate to find some peace, only to encounter more death and violence. There is even an episode that focuses on a young girl who is traumatized by the Zambot 3 because her parents died in the battle. It's not hard for the people to find a scapegoat, a reason why they're suffering from these indiscriminate acts of genocidal violence. As the patriarch of the Jin family, Kamikita Heizaemon, once said, people hate them because they haven't won the war yet.

We thus watch the Jin family, a symbol of the now disintegrating Ie-family structure, struggle to protect Japan. Their traditional family bonds are tested in the modern world of 1970s Japan, and their ways are seen as alien and not part of the Japanese narrative. When the Japanese people finally believe in the Jin family, it comes after a long period of resistance, and everyone is at the point of despair.

It's also hard for me to separate the Jin family from its kanji, 神 (which is usually read as kami). As Japan marches toward a nuclear family and a secular future (i.e., our present), it is reluctant to trust more traditional notions of community; and yet such calls may resurface at moments deemed politically useful and salient to the Japanese people. We see a modernizing Japan that no longer believes in the mythic power of the kami/Jin family, but they may return to these traditional/alien concepts when the time is right.

The anime constantly shows the dehumanization of the Jin family. Even when the country has finally accepted Japan as a major civilian power in episode 20, the first thing they do is take control of King Beal and the Zambot 3 because they don't believe in the family could actually fight.

This is a cynical, almost misanthropic vision of humanity for any work, let alone a show for children. The only people who recognize the Jin family as soldiers who are sacrificing their lives for the greater good are their close friends; everyone else treats them as villains or assets. It twists Kappei's super robot pilot personality into something darker: he goes from being a rascal to someone who tries to mask his frustration and trauma with his hot-blooded temper. He doesn't know how to respond to a humanity that rejects his loved ones or his cries to be loved.

Instead, he is objectified into a source of admiration and hope, not as a person but as a dehumanized symbol for our own purposes. He and his comrades are toys for our imagination.

The Revelation of Human Bombs

This all culminates in the penultimate arc where the main antagonist, Killer the Butcher, has instructed his goons to make bombs out of people. Butcher has always been characterized as a comedic villain, clearly inspired by gay stereotypes and villains of the time. He loves to find creative ways to murder people, and unlike his contemporaries in other shows, he often succeeds.

His diabolical plan is to exploit people's empathy: since everyone is fleeing to refugee camps, he has instructed his underlings to create fake refugee camps to kidnap people and turn them into living human bombs. They are then released into the cities in a state of forgetfulness. These walking bombs can only be distinguished by the star on their back, a fact that was discovered by chance by Kappei.

The episode in which the human bombs first appeared, #16: 人間爆弾の恐怖 (fan translation: The Terror of the Human Bombs), is a traumatic watch. Everyday people are being blown up in train stations, dams are destroyed, and even a plane carrying passengers explodes because one of the pilots is a human bomb.

It's clearly the most successful campaign Butcher has ever done, and it's hard for me not to think about how people used to talk about the so-called COVID superspreaders as walking bombs.

But it's much darker than the current pandemic we're in: there's no way for someone to recover after being implanted with a bomb. Even the Jin family, with all their technological wonders, have no solution. These people are finished. They have to die on the outskirts of Japan, or they could cause even more suffering.

These horrific scenes not only convey how close and personal the war has become, but also give Kappei less of a reason to fight. His family and friends, the people he has been fighting for since episode 1, are all dying. What gives him the strength to continue fighting for a human collective that will soon tire of his bravery?

We also get a glimpse of how powerless Zambot 3 and the Jin family are in certain parts of the war. They only know how to fight and lack the diagnostic tools to find out who has the bomb and help people recover. One episode in particular feels cynical: in #18, a friend of Kappei's escapes from the Galzok, and the first thing the Jin family asks her to do is show her back to the camera so they can figure out if they can welcome her back to the base. Fortunately, she didn't. But the same kind of welcome wasn't allowed for the one friend who was actually a human bomb -- she had to be quarantined away from Kappei, and he couldn't handle that. When she exploded without fanfare, all he could do was "ask" her why she was born when all she did was get chased by the Galzok and then die. The Zambot 3 is a tool of war, not of medicine.

In my view, the human bomb episodes shatter any belief that the Jin family is fighting for humanity. While we see everyday people suffering in the refugee camps and learn to understand their suffering, we see the Jin family suffering the most. They keep saying they are fighting for the greater good and the survival of Earth, but they are unable to explain their reasons to anyone. Humanity did not call on them to take up arms. And when the humans began to let go of their resistance, the Jin family learned that they weren't up to the task.

This is not to say that the Jin family is Machiavellian or opportunistic. Far from it: I think they're too pure. Like the Japanese children who were drafted to fight for Imperial Japan in World War II, they saw themselves as the only ones who can defend the country. I'm sure some of that must have been true at the time, but it becomes less and less coherent as the show goes on. Their cause is hollow, and they can only do so much to save the friends they love.

In the end, the Jin family is not soldiers but civilians. Japan was only saved because they happened to be there. Otherwise, there is no deeper meaning to their existence.

Galzok the Berserker

In the final episode, when all but Kappei and the "civilians" of the Jin family and friends have been wiped out, Kappei finally meets Butcher's boss, Galzok. Its true identity is Computer Doll No. 8, a brain-like machine designed to destroy all forms of evil life. It asks some pointed questions about the "reasons" he fought for such an evil race that is humanity, some of which have already been refracted in this essay.

There is an unsubstantiated but very believable claim that this antagonist is based on Fred Saberhagen's Berserker series.[^1] The following section assumes this to be true, not only because it is highly likely, but because I find it very interesting on how it diverges from Zambot 3.

The Berserkers are a non-living, robotic species programmed by their creators to kill all lifeforms. They first appeared in "Fortress Ship" (released as "Without a Thought" in Berserker). The story begins like this:

The machine was a vast fortress, containing no life, set by its long-dead masters to destroy anything that lived. It and many others like it were the inheritance of Earth from some war fought between unknown interstellar empires, in some time that could hardly be connected with any Earthly calendar.

One such machine could hang over a planet colonized by men and in two days pound the surface into a lifeless cloud of dust and steam, a hundred miles deep. This particular machine had already done just that.

It used no predictable tactics in its dedicated, unconscious war against life. The ancient, unknown gamesmen had built it as a random factor, to be loosed in the enemy’s territory to do what damage it might. Men thought its plan of battle was chosen by the random disintegrations of atoms in a block of some long-lived isotope buried deep inside it, and so was not even in theory predictable by opposing brains, human or electronic.

Men called it a berserker.

They can also appear as smaller robots and have learned to communicate with humans by kidnapping and experimenting with human brains. In "Starsong," the Berserkers learned to “culture” brains from their studies of human brains because they were deeply interested in their ability to think. They have also reprogrammed some human brains to simply compute algorithms, and that's all they can do -- such a brain, according to the narrator of the story, "seemed incapable of anything but going on with the job", and if it were still considered human life, euthanasia might be a more fitting end.

The Berserkers are a formidable enemy that has captivated science fiction writers ever since. As the highly opinionated Encyclopedia of Science Fiction states, "Berserkers soon became a significant icon of Genre SF, a myth whose cumulative force is perhaps more potent than any of Saberhagen's individual stories about them." It's also made a name for itself in discussions of Fermi's Paradox: What if the reason we're alone is because the aliens are all dead thanks to some Berserker probe?

But the Berserkers, at least in the early Saberhagen stories, are not meant to be existential threats, but gigantic obstacles that bring everyone together. Humans and their descendants are the only races that can fight these AI ships because they have a fighting spirit that no other alien species possesses.

In "Stone Place," the reader is introduced to Johann Karlsen, the newly appointed High Commander of Sol's defense. Karlsen is newly engaged to a woman he is in love with, though he admits it is part of a political marriage.

However, the planet she's on has been taken over by the Berserkers, and there are Venerians plotting to overthrow him. When his fiancée is rescued, she has been brainwashed and finds him frightening, only to flee into the arms of the POV character. She dies, however, in the victorious battle that marks the end of the story, and he realizes that part of the prophecy that says he will die owning nothing is true. And yet he turns to the people around him and proclaims that on the day he dies,

"I will remember this day. This glory, this victory for all men."

It almost seems that "only death could finally crush this man". The story ends with the POV character, a poet, returning to his work:

The world was bad, and all men were fools -- but there were men who would not be crushed. And that was a thing worth telling.

According to the Independent, Fred Saberhagen served in the US Air Force during the Korean War from 1951-1955. This may explain the very rich descriptions of being a soldier going in and out of shifts in novels like Brother Assassin (translated as 皆殺し軍団). And according to Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, he was also an editor for the Encyclopedia Britannica where he wrote the original entry for science fiction. He had lived an illustrious life, writing stories about how the violence within humans sparked life and thus resistance against the cold, lifeless machines.

Yes, humans can be destructive. Yes, humans can start wars. But the same warring nature of humanity creates the vitality of what makes humanity great. There is an almost Nietzschean quality to his writing: what appears to be the violent impulses of humanity is actually its expression of life, and we must say yes to that. Even pacifists have to acknowledge that.[^2] The war machines they develop during their many civil wars are, in fact, the only thing that can stop the Berserkers. The Berserkers allow humans to stop fighting each other and work side by side, even in shaky alliances, against this common enemy. It's a powerful mythic narrative about how people will succeed no matter what evil force they're up against.

There's one problem: "Stone Place" was not translated in time before Zambot 3 aired. In fact, the few clearly heroic stories Saberhagen wrote were not translated and published until after the show was over.

If we only read the stories that were translated before Tomino and his staff started working on the TV show, we get a picture of humans mostly losing to highly intelligent computer monsters, and that's it. There is very little hope, only despair that people are losing their meaningless lives for nothing. The small victories that the humans have achieved can only do so much.

So when the Berserker-style villain asks Kappei why he fought for a humanity that would reject him, Kappei had no Saberhagen-style answer. Instead, he could only reject its accusations in vain. His family and friends have died, and there's no answer to give their sacrifice any meaning.

As the ending song suggests, Kappei's only "rational" reason for fighting — his only coherent answer to Computer Doll No. 8 — is that this is the only home he has. His ancestors lost their home, all other habitable planets have probably been destroyed, only Earth is a home to him. He didn't fight for the humans who fought over his status, nor for some greater justice. Kappei just wanted to live in a home, a place that would never betray him. He fought not for humanity but to belong somewhere.

And in that sense, for a show that depicts so many displaced people as refugees, the Jin family are perhaps the biggest and most tragic refugees of all.

The Berserker in Zambot 3 is not an existential threat to humanity but to the idea of cooperation in face of war. Indeed, humanity never gets its shit together. They refuse to cooperate or would rather take control of the situation. Thus, the questions all revolve around the evilness of humans who will never be considerate, will never reciprocate, and will only abuse and exploit those who can help them. History shows that humans are a selfish race that will only feel be grateful when the tides of war are on their side.

This makes it impossible for me to see the Jin family as martyrs. I find myself reluctantly agreeing with Computer Doll No. 8. Kappei's indomitable spirit was ultimately used by the Jin family to protect a humanity that continually refused to acknowledge their existence. He was another child soldier who fought for Japan.

I felt empty when the people who had rejected Kappei ran to welcome him back into society. A Japanese writer described the crowd as an unthinking mass that reacts to situations when it best serves them. It's hard to know what their long term intentions are, but all we can really say is that the final montage is a mirror of who we are in reality.

There is an iconic shot of the battered Zambot 3 crying before the final montage. Its arms and legs are torn apart. The sun is setting. No one can hear or see this super robot that has done so much tearing up. It is emptied of the fighting spirit that Saberhagen saw in his human characters as it rusts away into the forgotten annals of history.

The Zambot 3 is also a toy.

On the Pixiv dictionary page for the Zambot 3 show, there is an unsourced quote from Tomino saying that after the finale episode aired, the production company, sponsors, and toy store owners were scared shitless. I have no doubt that it must be true: the grim finale is still unheard of in modern anime.

But the toys still sold well, even to the 1980s. According to the Japanese Wikipedia article on Zambot 3, someone claimed in the February 1978 issue of Toy Journal that Japan was experiencing some sort of boom in radio-controlled and transforming toy cars. It's also possible that Daitarn 3, which aired next, might have helped its sales.

There are also several commercials featuring the Zambot 3 toys that aired from 1977 to as late as 1982:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PlT7VBd4SGQ

These commercials do not contain the traumatic episodes depicting the Japan children know in ruins. The first shows the characters alive while later commercials drop references to these kids. None brings up the Gaizok. One particularly memorable commercial shows a real kid putting on Kappei's helmet and imagining they are a part of the robot fight.

This may be jarring to today's audiences. Did kids not watch the show where the toys came from? It's certainly possible, but from time to time people like Yokoo Tarou will comment on how they grew up watching the show. There is even a TV special that ranks Zambot 3 as having the third most disturbing finale to an anime.[^3] Surely, even if children didn't know their toys came from such a traumatic show, their friends might.

I don't have a psychological explanation for all of this, nor do I care. But I want to at least suggest why I might be interested in owning a Zambot 3 model for myself.

The Zambot 3 is like the ultimate symbol of a commodity. It is a vacuous symbol of poetic justice. Its existence undermines the belief that human beings can overcome any form of adversity.

The irony intrigues me in a morbid way. Unlike the Gundams which all feel like a blur to me because they're concrete and realized symbols of war, the empty and artificial content of the Zambot 3 fascinates me. It has tried to commodify the spirit of super robot shows, but there is nothing mythic inside this piece of plastic. And yet, this abyss of nothingness allows me to reflect on the futility of heroic sacrifice.

I see in this religious symbol the senseless struggle, the uncaring humanity of which I am a part, and the people who died in history to keep us alive. Capitalism allowed us to buy this sacred mirror to look at ourselves, or I could buy this for my nephew who's going to be two next year. The possibilities are endless as long as they are transactional in nature.

There is no life that we can speak of inside the Zambot 3 toy. It is simply a toy. Perhaps its success as a toy confirms the TV show's message: no one cares about the people who saved the world until they’ve proven their market value.

The fetishism of commodities and heroes has transcended any need to ground objects in historical or cultural spaces. No wonder the Zambot 3 cries: it knows it has become a revoltingly successful toy.

[^1]: Many blogs and the Japanese Wikipedia often mention this as some historical fact without citing any sources. I have not been able to find any public quotes from Tomino or any of his staff about this claim.

However, I find this somewhat credible when we consider how similar Computer Doll No. 8 and the Berserkers in the Saberhagen novels are. But I'm wary of confirmation bias especially since a section of the article hinges on this, so I tracked down the release dates just to be sure.

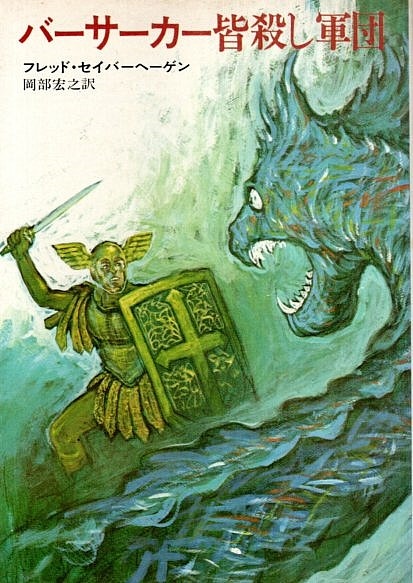

The first Berserker novel published in Japan at 1973 is surprisingly enough the second novel, Brother Assassin, translated as バーサーカー 皆殺し軍団. Reading the book does not adequately explain the gruesome nature of the Berserkers, though it is a very fun read. The book that introduced the Berserkers to the world, simply titled Berserker and translated into Japanese as 赤方偏移の仮面, was not published until 1980. However, stories from this book have appeared in one form or another in Hayakawa Shobou's SF Magazine, starting with the July 1969 issue, which published the first short story of the book, "Fortress Ship". By the time Zambot 3 aired in 1977, the staff might have read three short stories from the book (the aforementioned "Fortress Ship," "Patron of the Arts" in September 1969), and "Masque of the Red Shift" in March 1970), one short story that would appear in the upcoming book, The Ultimate Enemy ("Starsong" in June 1970), and the novel Brother Assassin in 1973.

While I cannot definitively say that the staff is influenced by the books, it is more than likely that they were able to follow the Berserker storyline if they subscribed to the magazine. Personally, I found the books to be enjoyable and insightful in understanding Zambot 3, and I would recommend that people seek them out if they are interested in the subject matter and what I have to say about it. They are enjoyable works of pulp fiction that remain timeless to my boomer brain.

[^2]: There is one Saberhagen story that deals directly with pacifism: "The Peacemaker". Unfortunately, it was untranslated when Zambot 3 came out, but I think it is worth mentioning in the footnotes.

In Berserker, the non-combat alien narrator introduces the story by recognizing that there are different ways to praise life. But nevertheless, they "intellectually" admit a certain "truth": "In a war against death, it is by fighting and destroying the enemy that the value of life is affirmed." The fighter will not need to worry about the health of their enemy. The pacifist, however, may feel differently: while the state of war may not affect the fighter, the pacifist's pacifism affects their own being. The narrator touches "a peace-loving mind, very hungry for life" and the story begins.

The protagonist of "The Peacemaker" decides to negotiate with a Berserker for peace. When he sees the holes in the Berserker's hull, he "felt a faint thrill of pride. We've done that to it, he thought, we soft little living things. The martial feeling annoyed him in a way. He had always been something of a pacifist." After a philosophical discussion about the spirit of life and the sentience of humanity, he seems to have convinced the Berserker to abandon the attack as long as he provides the AI with some human tissue to study.

Of course, this was all a ruse. The Berserkers probably escaped because they were too damaged to lead an attack, but they may have set a trap for the protagonist to unleash on humanity. Unfortunately for the Berserker, he provided his cancer tissue, and it turned out that the Berserker actually cured his cancer.

I read this amusing short story as a rebuke to pacifism for ignoring how human ingenuity thrives in the face of obstacles. While I don't share Saberhagen's politics, I admire his clever reversal of a pacifist character to make a point about how humanity's greatest weapon may be its creativity in times of struggle.

[^3]: As recorded by a blogger who recorded this special on Fuji TV. For those curious, the second most disturbing finale is School Days and the first Space Runaway Ideon.