City Of Sadness

26 9月 2023

so this is a movie i'm unsure how to recommend to people who aren't familiar with taiwanese history, but i found it very personal.

i'll just provide a little bit of context first: the chinese civil war was perhaps just as important as the second sino-japanese war (aka ww2 in china) for chinese people. at that time, the communists and kuomintang/nationalists were fighting and they'd keep on fighting if not for the japanese. after the second sino-japanese war was over, the civil war ensued raging on. i think about this civil war because my chinese indonesian family has ties to the chinese civil war and it's split the taiwanese and mainland sides from each other. it was only until 2004-ish when we heard that the taiwanese side is still around.

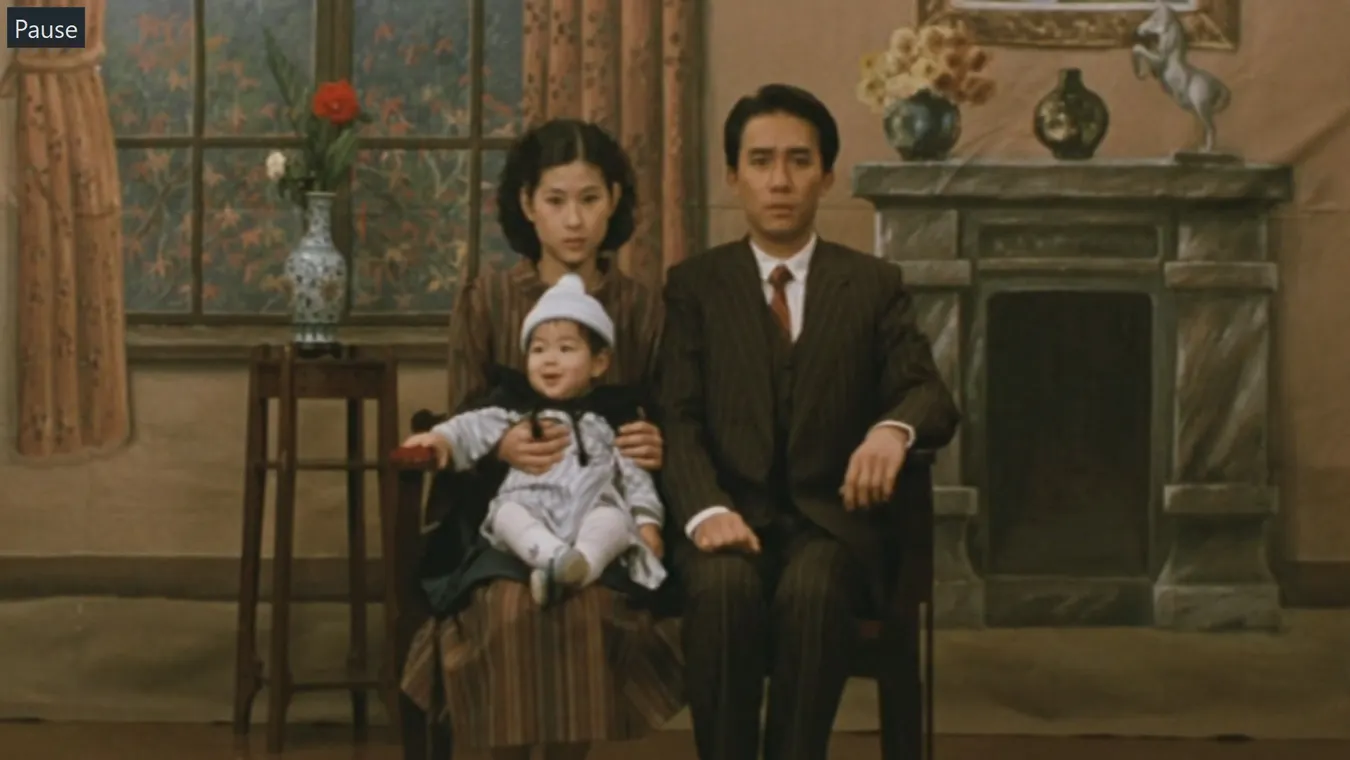

the film begins with the birth of a kid to the tune of emperor hirohito surrendering. later on, we are introduced to tony leung's character who has suffered an injury that's left him deaf. he's still happy though as a photographer. but as the movie continues, his family gets into troubles with the shanghai mob and also the rise of kuomintang.

this movie is historically significant for taiwanese cinema because it's the first to really go after the kuomintang being a fascist regime. many people know for good reason mao's atrocities in the great leap forward and the cultural revolution, but taiwan also faced something horrible too. chiang kaishek and his troops would "interrogate" people they suspect of having communist sympathies and "disappear" them, all while food prices increased dramatically. the people living in taiwan became oppressed and started doing large riots. indeed, this movie also features the February 28 Incident for the first time on the silver screen, though its egregious violence is not depicted. instead, we hear radio mutterings about what had happened. in a way, the movie is not concerned about the violence but the anxiety and responses to what's happening in taiwan. and when violence comes close, the few riots that do appear on screen appear horrifying.

one of the best scenes features the deaf protagonist being interrogated by one of these mobs. he's asked multiple questions -- where are you from? are you japanese? are you a mainlander? -- before he almost got whopped by a rifle. the movie is truly at its best when violence looks like it's going to happen.

but it's also a powerful movie only if you understand what is going on. the subtitles i got were pretty poor and the movie doesn't really depict any context. the first half explores the background of the February 28 Incident since it dealt with tobacco contraband, so if you aren't aware of this, you'd be confused why so much of the film dealt with this drama. there are also many characters on the screen and scenes can transition without any indication of how much time has passed. i do think this is a benefit to the movie -- it mimics so beautifully the anxiety of waiting for good news before being smacked by several instances of bad news -- but it's definitely quite hard to follow at times.

nevertheless, i think this movie is an accomplishment once you understand how the movie resists sensationalizing a real trauma taiwanese families faced. the director isn't interested in turning this film into some political propaganda either. it's solely about a family who went through this transition period and how they suffered through this hell.

this is a movie that speaks to taiwanese people whose relatives and grandparents aren't there anymore. it reclaims a trauma in their own words, not others. i don't expect people with few connections to taiwanese history to get it. it's not a movie for them. it's a movie for us and i think that's beautiful.

(Editor's Note: Published as a repost on the same day)

https://letterboxd.com/screeningnotes/film/a-city-of-sadness/

letterboxd is full of uh... let's just say "white people reviews", but i quite like this one since they've done some reading about the history and tried to appreciate the movie at good faith without BSing about how deep it is or demanding the movie explain itself to them.

(Editor's Note: This section is another repost on the same day)

i've found an ebook that analyzes how a city of sadness is framed and it rules

this movie's cinematography and editing fascinates me, so i've been looking around for interesting explainers and i stumbled upon this academic cc4.0 book that's enriching my understanding of the work. it brings up some historical context, but its real contribution is how it explains why the movie's shots have so much emotional resonance.

i particularly like this section on how the movie (and the director) avoids medium close-ups and prefers long shots for like everything:

In City of Sadness, the closest Hou’s camera approaches any character is from the chest up, what would probably be defined a medium close-up. It is a physical distance that translates into an emotional one as well. However, Hou’s films can be quite moving, and the lack of close-ups is (surprisingly enough) one of the reasons.

Medium close-ups of single characters are close enough to make facial expressions legible, but by keeping the camera away from the action, long shots emphasize the context among characters. By extension, this occasionally reflects a cultural emphasis on the family before the individual, deriving, in the last instance, from a long history of Confucian thought. This suggests that in American movies, our cultural obsession with individuality translates into a cinematic singling out by means of the close-up; narrative focus on a hero is complemented by the mise-en-scène. City of Sadness presents an alternative approach to mise-en-scène where, more often than not, the characters are seen (in long shot) in the context of other family members. In fact, the only true close-up of the film is of a photograph Wen-ching is touching up: a family portrait. Hou compounds his visual orientation toward the plural by diffusing the narrative attention among a number of characters. As in most of his other films, it is difficult to decide who the primary character is.

According to Hou, he began using long shots to cover for his nonprofessional actors. At the same time, he asserts that the long shot—combined with the long take—produces a special kind of image: “I’m not using the long shot just for the sake of the actors. A screen holding a long shot has a certain kind of tension, and for this you can’t find an alternative method to substitute. I realize I am confronted with a contradiction here” (Mart Dominic and Peter Delpeut, “A Man Must Be Greater Than His Films,” 16).

it's such a unique way in envisioning movies. this particular attention to space, the instability of transitions, and so on are all discussed in this book. you don't have to necessarily watch the movie to read this book, but i think it's one of the most interesting pieces of film criticism.

(Editor's Note: Final repost for the day)

from the conclusion of this book

It is true that we emphasize the aesthetics of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s filmmaking and how his style mediates the representation of politics, even to the extent of alienating many in the audience. However, we suggest that the discontent expressed by the audience and the political critics precisely reveals the problematics of filmic totality. So what drove the Taiwanese to fill theaters for City of Sadness? Hou’s film even outgrossed the simultaneously released Miracles—Mr. Canton and Lady Rose (Qi ji 奇蹟), Jackie Chan’s major 1989 production. It is likely that the Taiwanese craving for images and narrations of the February 28 Incident contributed to Hou’s commercial triumph over Golden Harvest’s major action-adventure film, the first time that a New Cinema filmmaker ever outperformed the kung fu megastar, Jackie Chan. But it is the denial of that desire—the scopophilia of massacre—that upsets viewers.

Hou’s thoughtful restraint in representing violence seems to indicate his ambivalence to the filmic image. Yet, it is this ambivalence that lends the narration of Taiwan dynamic complexity ... While perhaps Hou is not historically correct in depicting Taiwan’s society—as has been pointed out by many historians—and his disjunctive form of representation arguably discredits his politics, the film provides an excellent stage to discuss a nation that has historically developed a culture of hybridity, a state of multiple, colliding ethnicities and languages.

Had Hou provided those dissatisfied spectators direct images of the massacre in a style purged of ambiguity—the manner in which a popular film would treat this history—his film would likely have held none of its power. Hou probably would have produced a film analogous to the frightening clarity of the Nationalist Party, replacing one pedagogical monologism with another. However, by staging the traumatic memories of the nation through its charged spaces and double writing, the film re-presents history with all its uncertain multiplicities. Whether it enlightened its audience will be endlessly debated and is ultimately inconsequential. The film finally helped bring the February 28 Incident into public discourse and sparked discussions about the character of the nation precisely through its multiple entry points. The health of a nation—and a national cinema—depends upon being open to this complexity.

i agree with this conclusion. indeed, i've read western letterboxd reviews that don't get why the movie is actually depicting the February 28 Incident -- but its power comes from it being "around" it. its discomforting ambiguity and reluctance to turn into a simple misery porn narrative is what gives this movie its potency. i'm glad that i've had the privilege to think with the movie and this elucidating book.